In Longreach and the surrounding region, the pioneers lived a life shaped by hardship, resilience and ingenuity. When you come to Longreach for a holiday you will hear about some of these famous names and also about the everyday heroes who raised their families and livestock in challenging, remote conditions without the conveniences of modern life.

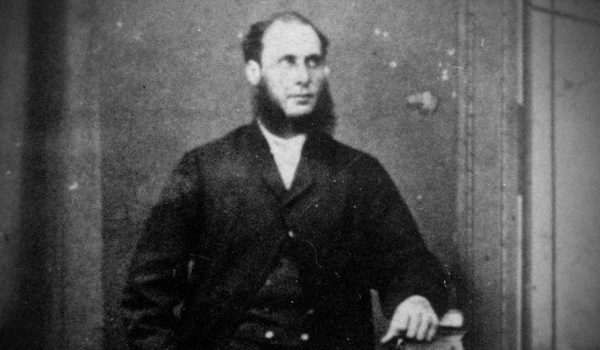

Captain Starlight (Harry Redford or Readford)

Captain Starlight (born Harry Readford) is a larrikin hero who started his most notorious adventure close to Longreach on what was then the Bowen Downs Station. Although he was a cattle duffer (thief), his cheeky plan and excellent bushmanship endeared him to ordinary people in his own time and ever since. His incredible journey from Longreach to South Australia with over 1000 stolen cattle has gone down in the history books.

At Nogo Station you can see the ruins of stockyards where he is said to have branded some of his stolen cattle before starting the journey south. You can discover the whole story in the Outback Pioneers Starlight’s Sound & Light Spectacular Picture Show with an exclusive movie commissioned by the Kinnons.

Photo courtesy of modernfarmer.com

Banjo Paterson

McGinness and Fysh

Although not as well known as Captain Starlight or Banjo Paterson, Hudson Fysh and Paul McGinness were at least as important in Australia’s history. Having flown together in World War 1, these two men surveyed an air route across northern Australia in 1919 using a Model T Ford. They then founded Queensland & Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd (QANTAS) in November 1920. The fledgling airline’s first office was in Winton but soon moved to Longreach where the two men flew the first passenger and mail services from Longreach to Cloncurry and Longreach to Charleville in 1922. You can discover more about the pioneers of flight at the Qantas Founders Museum in Longreach.

Photo courtesy of qfom.com.au

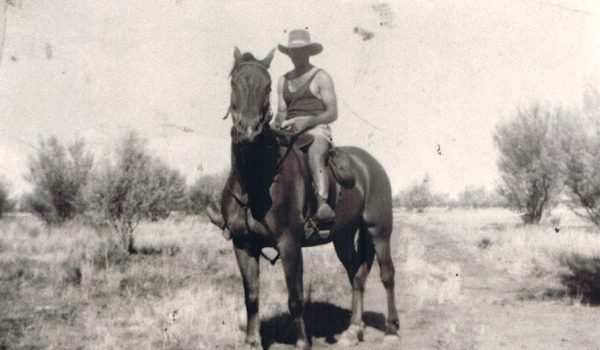

The stockmen and stockwomen

Without the horsemanship of the stockmen (and, in time, stockwomen), it would not have been possible to manage the huge cattle and sheep stations of the region. Many Indigenous people also worked on the stations and became part of this outback tradition. Although quad bikes and even helicopters have taken over some of the horse’s duties, the stockmen and stockwomen are still an iconic part of outback life. You can discover their story at the Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame in Longreach.

Photo courtesy of Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame outbackheritage.com.au

The shearers

The women of the homestead

Outback pioneer women were (and are!) a very special breed! With the menfolk often away for days or weeks at a time, mustering, droving or maintaining the hundreds of kilometres of station fence-lines, the women typically stayed at home to raise their families, manage the workers, maintain the kitchen garden and homestead animals. Far from hospitals, schools and services, the woman often had to be a nurse, midwife, teacher, dressmaker and cook. And she had to be able to mend a water pump or deliver a calf too! These days, women have taken on traditional men’s roles on some stations but, whatever the role, outback women need strength, resilience, self-reliance and a sense of humour!

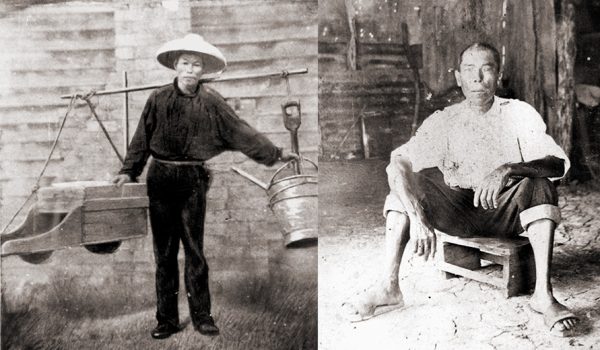

Chinese pioneers

After the Australian gold rush, many Chinese miners stayed on. They had an important role in the pioneering years of western Queensland, helping clear land and dig dams. They also helped as cooks, shepherds or labourers on outback stations. Their skills with irrigation and land management enabled them to create productive market gardens in the dry land, where they produced a range of vegetables and fruit. In Longreach, ‘China Town’ was at the lower end of Eagle Street towards Black Gin Creek. There were five Chinese gardens in town supplying the local people with fresh produce and helping them avoid the illnesses that some pioneers suffered. They were business people too. Jimmy Ah Foo built the Federal Hotel and was the popular owner of it in the 1890s. He had 13 children, who formed a family band that played for hotel patrons.

Indigenous stationhands